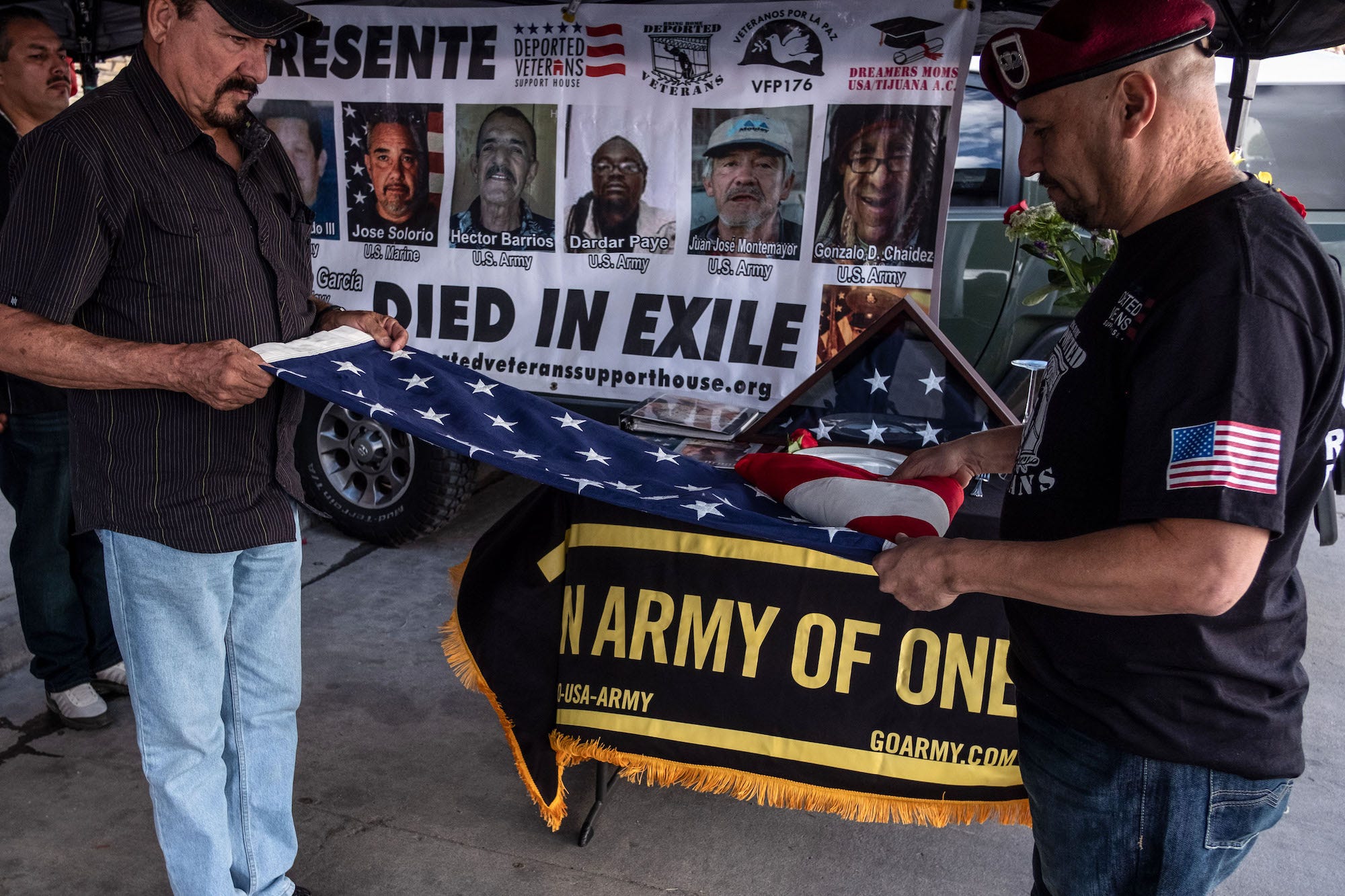

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

- For thousands of US veterans who have been deported to Mexico, the strain of being separated from their home is compounded by threats from criminal groups that seek them out for their military training.

- The election of President Joe Biden has given some of those veterans renewed hope that there will be a chance to return, but for others who have already restarted their lives, that hope comes too late.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Ciudad Juarez, MEXICO – Thousands of US veterans deported to Mexico, some of whom have been forcibly recruited by cartels, are asking the Biden administration to let them “back into their country.”

On a letter to President Joe Biden, the Deported Veterans Support House, writing “on behalf of thousands of US deported veterans,” asked Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris to stop deportations of US veterans and to welcome back those who are already on foreign soil.

“We believe that there is not a more perfect time in our nation’s history to bring these heroes home. President Biden is a military father and knows what it is like to be separated from a loved one overseas,” states the letter, which was obtained by Insider.

The letter, also signed by Sen. Tammy Duckworth and Rep. Mark Takano, addresses a darker truth.

“In Mexico, drug cartels prey on this desperation, coercing former service members to join criminal operations for their combat skills,” the letter says.

Hector Barajas, founder of the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana and a US Army veteran, expected the letter to encourage thousands of veterans currently stuck in foreign countries.

REUTERS/Jorge Duenes

"This is the first time we write a letter to the President of the United States. I really hope they understand the problematic and the risks we take by being deported to a place we don't really belong," said Barajas, who was granted US citizenship in 2018 after 14 years of waiting.

One of those risks is forcible recruitment by Mexican cartels.

"The recruiting by Mexican cartels is real. They are looking for professionals with training on the use of arms," Barajas said.

He believes his advocacy on behalf of deported veterans is the reason he has never been approached by cartels. But not everyone is that lucky.

"Mike," a deported US veteran, is currently facing more than 50 years in Mexican prison after being accused of several murders related to his work for a cartel.

"I was deported back in 2010 after serving the US Army and deploy[ing] two times. Since then I'm working with a criminal organization." said Mike, using a pseudonym to avoid retaliation.

Mike said he was recruited specifically to assassinate rival gangs and to train young sicarios as soon as he was deported to Ciudad Juarez, which borders El Paso, Texas.

"I was totally scared when I got deported. They reached out to me on the streets, and they knew I had a kid and threatened me with harming him if I didn't cooperate. So I started training them on how to shoot and clean guns," he told Insider.

Mike said he didn't know of any other US veterans working for the Juarez cartel, but Jose Camacho, a 65-year-old US Army veteran deported to Mexico, said many more like him and Mike are working with Mexican criminal groups.

"There are many more. I know of a few working for the same organization, but it wouldn't be news to find many, many more even [with] other organizations through[out] Mexico," he said.

GUILLERMO ARIAS/AFP via Getty Images

Camacho was deported around the same time as Mike, after being arrested for drug trafficking in Texas. After that, he started collaborating with the Juarez cartel.

"They would pay me to teach members on how to use weapons and to teach them on ambush and tactics I learned in the Army," Camacho said. Camacho says he is no longer involved in any criminal activity.

The number of US veterans who have been deported, let alone those working for criminal organizations, is currently unknown, but deportations have been going on for some time.

"Through the Deported Veterans Support House I've helped around 400 people since 2003, but deportations for veterans started back in 1996," Barajas told Insider.

A 2017 report from the National Immigration Forum said about 40,000 immigrants serve in the US military and about 5,000 non-citizens enlist each year.

During his campaign, Biden addressed the deportation of US veterans several times. At a CNN town hall in 2019, Biden promised "to bring them back."

"That's why we're who we are, the country we are. We are a country of immigrants, and they serve, and they should be treated the same way," Biden said.

Biden echoed that sentiment in an official campaign statement on veterans:

"Biden will not target the men and women who served in uniform, or their families, for deportation. He will also direct the Secretary of Homeland Security to create a parole process for veterans deported by the Trump Administration, to reunite them with their families and military colleagues in the US."

GUILLERMO ARIAS/AFP via Getty Images

But those promises don't give much hope to veterans stuck south of the border.

Michael Evans, a 32-year-old US veteran deported in 2009, said he has put down roots in Mexico and even if there is an opportunity to return to the US, he is not sure he will take it.

"I just submitted papers to become a US citizen and see what happens. I want to be a US citizen and to have that option, but honestly I'm not sure if I want to start a new life over again," Evans told Insider.

For Evans, what Biden or any other president says isn't enough for a change in faith.

"I've heard President Biden saying he will fight for deported veterans, and I hope he will, but I'm skeptical because of the system overall," he said.

Evans, currently living in Ciudad Juarez, said he has never been approached by criminal organizations but is aware of how they operate in Mexico.

"I don't think they will get to you if you are not close to them. You have to be around them to receive an offer or a threat," Evans said.

Evans might get a second chance to become a US citizen and return to the country he served. But for others, the hope of getting home under Biden comes too late.

"I don't even think about it. This is the life I'm living today. If some of them [deported veterans] are getting back to the mainland, well, good for them, but as for me, it's too late now," Mike said.

Dit artikel is oorspronkelijk verschenen op z24.nl